Sidney was not one of those young men who rushed to join the army as soon as war was declared in 1914. Indeed, he was thirty three and didn’t enlist until 1916. I wanted to know the circumstances surrounding his enlistment and began by looking at the government’s plans to increase the numbers of service men in the army and navy after war was declared.

Conscription

In the first two months following the declaration of war, almost half a million men (including boys who lied about their ages) volunteered to join the army.

Almost 40 percent of the volunteers were rejected on medical grounds with malnutrition being rife amongst young working class boys, many of whom did not achieve the required height but, by the end of the first year, two million men had joined the army.

Unfortunately, the initial rush to enlist meant that many key workers from essential occupations joined the army, which led to such occupations being identified and at least a further 1.5 million men not being allowed to enlist.

It was clear that the number of volunteers could not continue at the same rate but many politicians were ideologically opposed to conscription, including the Prime Minister, H H Asquith but, by early 1915, the government began to seriously consider conscription.

The usual ten yearly census had been carried out in 1911 but the government needed to know how many men of military age were still civilians, their occupations, how many could be spared for war work and how many could join the army.

On 15 July 1915 the National Registration Act 1915 was passed, requiring that all men and women between the ages of 15 and 65 years of age register at their residential location on 15 August 1915.

The forms required that the occupations of men “should be stated with the utmost care in all cases, but especially by persons having technical knowledge of skill, such as workers in engineering, ship building and other metal trades, and by persons engaged in agriculture.”

When completed the register contained the names, ages and addresses of over 5 million men who were not yet in the forces, of whom over half were married or widowed. Of the single men, 690,183 were noted as being in ‘starred’ roles, meaning they were in coal mining, munitions work, railways, some agricultural work or other essential war work.

The bill was pushed through parliament as a way of dealing with the labour crisis, allowing the government to better deploy the labour force but many feared that the register would be used for military conscription, as proved to be the case.

Initially, military recruitment officers would make up to three visits to each of the single men who were not noted as being in essential war work. They would inquire about the reasons why the men had not joined, aiming to pressurise the men to enlist.

But even this was not enough and conscription was introduced in 1916 with the single men not in essential war work being the first to be called up.

The Military Service Act 1916 brought conscription into effect, for those men aged 19 – 40 who, on 2 November 1915, were unmarried or were widowed without dependent children and who did not hold a certificate of exemption.

Sidney Herbert Martin was born on 3 July 1881 and was thirty four in November 1915. He was a dock labourer and a widower.

His second child, Rose Beatrice had died of pneumonia the year before but his first daughter, Irene Beatrice may have been living with her grandparents at the Robin Hood Hotel in Bristol Road (as she had been in 1911).

His son, Sidney Herbert Langford Martin, by Annie Eliza Langford, was born in February 1914. Although the birth certificate appears to indicate otherwise, Sidney and Annie were not then married. However, he was a widower and presumably could list Irene and Sidney jnr as dependent children and thus avoid the initial conscription draft.

But, by May 1916, the bill was extended to married men (and presumably widowers) irrespective of dependent children and on 10 August 1916, Sidney enlisted as a private at the Royal Marine recruitment depot at Deal. His register number was PO/1556/S.

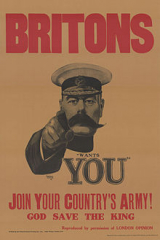

The PO stands for Portsmouth Division and the S for Short Service, which had been introduced in August 1914 on Lord Kitchener’s instructions. Standard army terms were to enlist for twelve years but a new form of ‘short service’ was brought in, under which men could serve for three years or for the duration of the war, whichever was the longest. The men enlisted under this scheme became known as “Kitchener’s Army”.

Service Record

For information regarding Sidney’s service, we have gathered details from:

The Royal Marines Registers of Service Index 1824 – 1925, held at the National Archives,

the Royal Naval Division 1914 – 1918 and the Royal Marine Medal Roll 1914 – 1920.

Sidney’s date of birth was noted as 27 May 1880 but we know that he was born on that date in 1881. He was a dock labourer, noted as 5 ft 9 1/4 inches tall and his mother, Mary Ann, 129 Tredworth Road, was given as his next of kin. The Registers of Service form records Sidney’s conduct as being very good throughout his service.

We don’t know why Sidney chose the navy rather than the army. By 1916 he was far removed from his mariner ancestral roots but perhaps his genes still felt the call of the sea.

The Royal Naval Division carried out its own recruitment programme and perhaps the recruitment poster influenced Sidney’s choice. No matter how or why, on 10 August 1916 Sidney enlisted at the RND Depot at Deal.

The Depot provided elementary training and training in discipline and Corps traditions.

From there Sidney was transferred to Victory RM BDE at Portsmouth, Hants. This was the pay and administration centre for all men serving in the Royal Marine brigade of the Royal Naval Division (RND).

Sidney was transferred to the 1st Royal Marines battalion on 18 December 1916 and, in the absence of his full records, I must assume that he joined the 63rd Royal Naval Division’s Infantry Base Depot at Beaumaris, Calais.

It received men and officers for all units of the Division, training the reinforcements before sending them on to join their units and also working with those who were convalescent from the front, retraining them for other work in the field if they were no longer fit to be in the front line trenches.

Sidney was one of 114 officers and 2651 NCOs and men who arrived as reinforcements for the 1st RMLI between 10 June 1916 and 15 December 1917, which gives some idea of the casualty rate sustained by that battalion alone.

The 1st and 2nd Royal Marine Light Infantry (RMLI) consisted of naval gunners and infantry soldiers and formed the marine battalions of the Royal Naval Division.

He served with the battalion, which was part of the British Expeditionary Force to France and Belgium, until he was taken prisoner on 28 April 1917.

Sidney was repatriated to Headquarters on 5 January 1919 and transferred to Portsmouth on 5 March.

On 6 April he was granted a war gratuity of £15 * and was demobilised on 9 April 1919.

Four weeks later Sidney married Annie Eliza Langford (the mother of his son Sidney Herbert Langford Martin) in Gloucester.

Just a year later, Sidney died on 15 May 1920, in Gloucester aged 39. He was awarded the British War and Victory Medals, which were issued to Annie Eliza, his widow, after his death.

Sidney Herbert Martin in France

So we know that Sidney served in France and was taken prisoner on 28 April 1917 but where exactly was he? Why was he there, at that particular time in the war?

By researching the whereabouts and engagements of the 1st RM battalion and, in particular, the 1st RMLI, together with the date on which Sidney was captured, we can determine the probable events which befell him between 18 December 1916 and 28 April 1917.

My conclusion has been confirmed by a Curatorial Volunteer at the Fleet Air Arm Museum, which holds many of the records of the Royal Marine Light Infantry but not those of the WW1 short service men of Portsmouth Division. Those records are held at The National Archives and I have obtained copies of the papers.

Royal Navy Division

When war broke out in 1914, the Royal Navy found itself with Royal Navy and Royal Marine reservists and volunteers who were not needed for service at sea but who could be trained to fight for ports or naval installations and then defend them. Thus a reserve stoker or a marine might find themselves not allocated to a ship but trained to act like infantry.

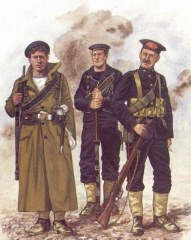

Two Royal Naval Brigades were formed. “They used naval rankings, naval uniforms and insignia, and observed naval traditions. There was a strong esprit de corps and the men considered themselves elevated above the common foot soldier. Each brigade consisted of four battalions, which were named after British heroes of the seas, not numbered as in the army.” http://wereldoorlog1418.nl/RND-Royal-Naval-Division/index.html

There was an existing Royal Marines Brigade, with four marine battalions which were named after the towns of their depots: Chatham, Deal, Portsmouth and Plymouth. They were closer to the army and had army ranks. Hence, when Sidney Martin enlisted, he became a private in the Royal Marines Light Infantry, 1st Royal Marines Battalion, Portsmouth Division.

The two Royal Naval Brigades and the Royal Marines Brigade were merged, becoming the Royal Naval Division, an infantry division. The idea for the RND had come from Winston Churchill, then First Lord of The Admiralty and it was dubbed “Winston’s Little Army”.

“The Royal Naval Division was regarded as an elite unit, tasked with ‘the hardest nuts to crack’ on the battlefield. Its personnel were inspired by great British Naval traditions, a high reputation and a personal sense of pride in their Battalion and Division.” FindMyPast.co.uk

The RND fought at Antwerp in 1914 and Gallipoli in 1915.

The 63rd (Royal Navy) Division

Having sustained many losses among the original reservists and volunteers, in 1916 the division was transferred to the army as the 63rd (Royal Navy) Division with three Brigades, the 188th and 189th comprised of the navy or marine personnel and the 190th were soldiers from the army. The two battalions of 1st and 2nd Royal Marine Light Infantry, together with two battalions of the Royal Navy Brigade formed the 188th brigade.

The Admiralty had preferred to place the Division under the command of the army rather than have it disband but the navy personnel retained their legal status as sailors and they wore khaki uniforms but with navy insignia.

From May 1916, the 63rd (Royal Naval) Division fought on the Western Front in France – the continuous line of trenches which stretched from the Belgian North sea coast to the French/Swiss border.

After fighting in the Mediterranean, including at Gallipoli, the 63rd (RN) Division landed at Marseilles and by October 1916 was some 580 miles further north, in the area of the Battle of the Somme, which had been raging since July. The Division went into intensive training and preparation for the next stage of the battle, which was to widen the base on which the army was advancing, to attack north and south of the river Ancre.

“Owing to the mud, bad drainage, and generally unhealthy conditions of the camps many men were taken seriously ill and removed on stretchers and unless the bearers could keep on the single plank they sank knee deep in the mud; this affected the strength of the Battalions considerably….”

When they reached the places from which they were to attack, the two RMLI Battalions found “…there was plenty of rain and they had no coats as they were purely in battle order, and water for washing was very scarce and mostly obtained by breaking the ice at the bottom of the shell holes; many availed themselves of the old Marine privilege and grew beards. The rum issue was very welcome but someone in authority had a brain wave and issued pea flour every alternate night instead of the rum, much to the disgust of the ‘Royals’. Occasionally they succeeded in killing a hare which with a few carrots and turnips made a pleasant addition to the rations, and on November 7th it is noted that an issue of cardigans was made which were very welcome.”

From “Britain’s Sea Soldiers”, see sources

The Battle of Ancre

The attack was planned to begin early on the morning of the 13 November. The length of front allotted to the 63rd Division was 1200 yards, their right being on the north bank of the river Ancre which ran due east to Beaucourt. Their objective was Beaucourt and the intervening positions; the trenches from which they were to advance ran north to south.

“The two RM battalions spent the night in the headquarters dug-out and the well known Cook-Sergeant, Jerry Dunn, of the 2nd battalion saw to it, with his yarns, that they passed a cheerful night, and gave them hot cocoa before they started for the attack in the morning.”

There was a thick mist in the morning and it was very dark when the first wave moved off at 5.45 am. The enemy barrage did not do much damage to the right and right centre battalions but fell heavily on the 1st and 2nd RMLI as they started. Every company commander in 1st RMLI was killed before crossing the first German line.

The Battle of Ancre, from 13 -15 November 1916, was intense and the losses were severe. The 63rd Division alone lost approximately 3,500 casualties, with the 1st RMLI having had 47 killed, 210 wounded and 85 missing. Of the 23 officers, 6 were killed, 12 wounded and 3 missing.

After the battle, military operations were mostly suspended as both sides were concerned with surviving appalling weather conditions, mud fields, waterlogged trenches and shell holes, coping with corpses and broken equipment. Little could be done beyond holding the line and frequently relieving the troops who found the physical and mental strain almost unbearable. It was these conditions in which Sidney would have found himself when he arrived to join the severely depleted 1st RMLI Battalion for his first experience of the war.

The Division remained in the Ancre area, with the 188 Brigade (including 1st and 2nd RMLI) and the two other brigades taking part in a number of attacks on the enemy lines between 11 January and 13 March 1917 including a two day action at Miramount on the 17 and 18 February. The operation was successful but of the 16 officers and 500 men of the 1st RMLI who had commenced the attack, only three officers and 100 men remained fit for duty.

From 22 February until 19 March both the 1st and 2nd RMLI were occupied in re-organising, providing working parties on the roads and in training. They left the area on 19 March and marched to Labourse. With the ground and weather conditions, it took them until 30 March. The march was exhausting as they experienced bitter northerly head winds and the men’s kit and equipment weighed about 96 lbs.

The Battle of Arras

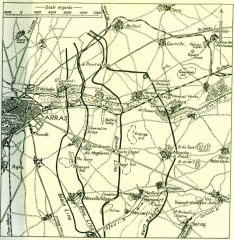

Labourse was about 18 miles north of Arras, a town never far from the front line and where the next offensive was planned. It was part of a wider plan for the British and French to achieve a strategic break through the Western Front.

Key to this was the capture of Vimy Ridge which had been heavily fortified by the Germans, allowing them to keep control over the surrounding territory. The task was given to the Canadian army with support from the British artillery.

The Royal Naval Division was moved a few miles further south, back into the Angres area, to the front line, to take their share in the battle to come.

From 9 April to 16 May 1917, British troops attacked German defences near Arras. The plan was to divert German troops from the French front and to take the German-held high ground that dominated the plain of Douai. This would start a week before the French launched an offensive along the Aisne River.

“The British plan was well developed, drawing on the lessons of the Somme and Verdun the previous year. Rather than attacking on an extended front, the full weight of artillery would be concentrated on a relatively narrow stretch of 11 mi (18 km), from Vimy Ridge in the north to Neuville Vitasse, 4 mi (6.4 km) south of the Scarpe river. The bombardment was planned to last about a week at all points on the line, with a much longer and heavier barrage at Vimy to weaken its strong defences. During the assault, the troops would advance in open formation, with units leapfrogging each other to allow them time to consolidate and regroup. Before the action could be undertaken, a great deal of preparation was required, much of it innovative.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Arras_(1917)

On 9 April, the British First and Third Armies launched the Battle of Arras whilst the Canadians began their assault on Vimy Ridge. It had previously been subjected to an intense allied bombardment lasting three weeks, taking some 80% of the German batteries out of action and cutting their supply lines to the trenches, leaving the enemy short of food, water and ammunition.

Despite the un-seasonal sleet, snow and cold, the Canadian assault was successful with most of the Ridge in their hands within two hours though Hill 145, which had not been subjected to the same preliminary and intense bombardment took longer to subdue. But, by 12 April, the Allies were in command of the whole of Vimy Ridge and it remained under their control for the rest of the war.

The capture did not lead to expected further advances as the French offensive which followed, despite involving more than 1 million men, made very few gains and incurred massive casualties.

Whilst the Canadians were involved in the Battle for Vimy Ridge, the British launched their own attack in the Arras area.

The First Battle of Scarpe, 9 – 14 April, was succesful, achieving most of the objectives, which the British were able to consolidate and then move forward, though they sustained heavy casualties. There followed a period during which the immense logistical support which was needed to keep the armies in the field caught up with the new situation, building temporary roads across the churned up battlefields, bringing up heavy artillery and ammunition, food for the men and feed for the horses.

The 63rd Division had been held back as part of the First Army’s reserve but on 14 April it began taking over the line in front of the village of Gavrelle, north east of Arras.

In the Second Battle of Scarpe, 23 – 24 April, in markedly improved weather conditions, the British troops attacked to the east along approximately 9 miles on both sides of the Scarpe River, from Croiselles to Gavrelle.

On the left of the main British attack, the Royal Naval Division was ordered to take Gavrelle. The 189th and 190th Brigades made rapid progress against Gavrelle and secured the village, though not without fighting a dogged battle from house to house and sustaining losses of over 1,500 men. The 63rd Division took 479 German prisoners.

However, there was a reinforced German position at a windmill, on high ground to the northeast of the village and when the soldiers and sailors tried to move forward from the village, as soon as they tried to leave the cover of the buildings, they were swept by machine gun fire. And so the commanders on the spot decided to settle for what they had rather than make for their objective just 300 metres away.

The two RMLI battalions had not been involved in the taking of Gavrelle on 23 – 24 April but were brought in on 26 April to relieve those who had been and to continue the British attack towards the windmill, which stood out very clearly on the skyline.

On the 28th they were detailed to carry out the task of advancing the line. Coming out of Gavrelle, the 2nd Battalion Royal Marines were to advance northwards along the Gavrelle-Fresnes Road whilst on their left the 1st Battalion Royal Marines had to advance up as far as the German trenches in the Oppy Line and then continue eastwards until they met up with their fellow marines.

Behind them the 1st Battalion HAC were held in reserve and the Anson Battalion were to push slightly forward out of the village to complete the new defensive position.

Battle of Arleux

“The purpose of the attack of the 28th was as a supporting role to the Canadian Corps and the 2nd Division attacking to the north. The RND were required to form a defensive flank for the 2nd Division on its left thus protecting its right flank. The 2nd Division and the Canadians were trying to breech the Arleux loop German defensive system. Gavrelle was part of this defensive system but the RND’s role was purely a supportive one. The Arleux loop was the last formed defensive system in front of the partially completed Siegfied Line, breaching it therefore would therefore jeopardise the Germans defensive plan.” http://www.royalnavaldivision.co.uk/?page_id=10

At 04:25 hours on the 28th April the two Marine Battalions launched their very separate attacks. Sidney’s battalion, the 1st RM, found that the wire in front of the German lines had not been cut; many men settled in shell holes in front of the German line and conducted the firefight from there. It seems some men must have got through because members of the Royal Flying Corps could see isolated pockets of marines behind the German lines and reported signal flares from the 1st RMLI sector.

However, almost immediately after the attack had been launched all communication with the 1st RMLI was lost though and, to all intents and purposes, the 1st Battalion were never heard of again.

The only form of news was from the few wounded who managed to get back to their own lines. They reported that the first two waves of 1st RMLI had got to their objectives but were then hit hard by a massive counter attack from the direction of Oppy wood, to the north. There was severe hand to hand fighting and gradually one small group after another was overcome, either being killed or forced to surrender when their ammunition ran out.

“The HAC were ordered to bomb their way up the Oppy line and succeeded in capturing the strong point, but it was too late for the marines who could not be found. Shortly afterwards the Germans recaptured their position.

“The 2nd RMLI Battalion managed to gain some territory including the all important windmill but by the evening the captured ground was back in the hands of the Germans with the exception of a small garrison who were hanging on for grim death at the windmill.”

http://www.webmatters.net/txtpat/?id=213

“A fierce battle continued throughout the greater part of the 28 and 29 April. The Germans delivered determined and repeated counter-attacks. The British positions at Gavrelle alone were attacked seven times with strong forces, and on each occasion the German thrust was repulsed with great loss by the 63rd Division.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Arras_(1917)

It is now known that the Germans regarded the windmill as of more importance than even the village itself and, evidently, they had no intention of giving it up easily.

The publication ‘The War Illustrated’ featured in its edition of 7 July 1917 a drawing of the fighting for the windmill. The description read:

‘Stubborn contest for the possession of Gavrelle Windmill, one of the many heroic episodes of the fighting along the Scarpe. Mr. Philip Gibbs, in his vivid account of the final capture of the mill by the British, says that again and again “the old windmill beyond the village changed hands. Eight times the Germans who had dislodged our men were cut to pieces or thrust out, and then our men finally held it.”

The capture of the Windmill position rendered this portion of the line secure for many months but at considerable cost.

The fighting at Gavrelle claimed 3,000 casualties from the Royal Naval Division. In particular, the losses of the Royal Marines Light Infantry were severe, with 850 casualties and many dead. 1st Royal Marines Light Infantry lost most of their officers and more than half of their men.

Sidney was with the 1st Royal Marine Battalion at Gavrelle. He was captured by the Germans on 28 April 1917, when the Royal Marines sustained their heaviest ever losses in a single day’s fighting.

Of the 1st RMLI, 6 officers were killed in action, 7 were wounded and 1 was taken prisoner. 157 other ranks were killed, 153 wounded and 28 were taken prisoner. Of the 2nd RMLI, 6 officers were killed and 3 taken prisoner. 155 other ranks were killed, 157 wounded and 173 taken prisoner. The ratio of killed to wounded is 50/50, which bears testimony to the ferocious nature of the fighting. Most certainly, there was no shame in being captured by the Germans on that dreadful day.

Nor can there be any shame in the failure of the 1st RMLI to complete its mission and to achieve all its objectives. It fought gallantly but was up against problems not of its own making. Not only had most of the wire along the route not been cut by artillery fire, thus meaning that most of the marines could not get through and were caught in a firefight in front of the wire, but it seems the attack was under provisioned.

In his analysis and summary after the attack, Brigadier General Prentice was scathing about the information which had been given to him when plans for the action were being drawn up. With regard to the attack by 1st RMLI he states “The enemy undoubtedly had reserves ready for the counter attack and were evidently much stronger than I was given to suppose by the BGGS of the 13th Corps, when discussing the operations at my headquarters, previous to the issue of orders by Division”. This firmly suggests that the opposition was thought to be weak at the time of planning and hence the size of the attacking force was reduced.

And yet, in the orders given by HQ to the supporting Machine gun section, the point is made that “All indications and information lead to the assumption that the enemies troops have orders to oppose strenuously our advance on the north bank of the Scarpe, which, if successful not only brings us up to the Siegfied line before it’s completed but also threatens his hold on Lens. Violent counter attacks must therefore be expected and will probably develop very shortly after we reach our final objective.”

And it seems that, in making his plans, Brigadier General Prentice had intended to place a battalion to the south of 2nd RMLI, to protect its flank, but that this had been vetoed by HQ.

So 1st and 2nd RMLI, together with the other battalions of the RND, suffered severe casualties which might have been avoided if intelligence held by HQ had been properly disseminated to the man charged with planning the attack. No wonder he was scathing in his report.

The Royal Naval Division lost many of the survivors from Gallipoli, Ancre and Miramount including many of its officers. It meant a core of experience was wiped out . The RND was rebuilt and went on to further battles but for Sidney the fighting was over. He spent the rest of the war in a German prisoner of war camp.

Prisoner of War

The International Committee of the Red cross holds three records pertaining to Sidney’s time as a prisoner of war. The records are in German.

There is no indication of whether or not he was wounded but they confirm:

- his name, rank and number:

- Sidney H Martin, Private, 1556, 1 RM LI company B,

- the date and place he was taken: 28.4.17 at Arras,

- date and place of birth: 27.5.80, Treadworth,

- next of kin: Sister, Mrs Hickman, 129 Tredworth Road, Gloucester.

If I am interpreting the records correctly, it seems that:

- In June 1917 Sidney was at the camp at Dulmen, apparently having arrived there from Lille.

- In July 1917 Sidney’s details appear on a page headed Limburg, noted as held at Et. Kdtr Douai (the rear echelon command centre at Douai). [However, as Limburg was one of a number of camps which were used as a registration camp, he may not have actually been held there.]

- By October 1917, Sidney appears to have arrived at Heilsberg from Dulmen. [Which seems to indicate that Limburg was only the registration centre.]

Douai is on the river Scarpe, 16 miles from Arras, 25 miles from Lille. It is not clear if the centre at Douai and the place noted as Lille actually referred to the same place.

Heilsberg was about 80 miles east of what is now Gdansk, in Poland. It was the most easterly of the German prisoner of war camps. There were sub-camps and work locations. By October 1918 there were over 95,000 prisoners, of which the majority were Russian. There was one British officer and 997 men. 39 British men died between August and December 1918, aged between 19 and 36, including a private from the 2nd R.M. Battalion.

At the beginning of the war, each Division had formed a Comforts Fund to supply men overseas with articles of warm clothing and to help with a few extra luxuries and Christmas presents but soon after the Antwerp expedition it had become apparent that there was a far more serious task, that of providing clothing and food parcels for the unfortunate men who had become German prisoners.

Without this work, it is undoubted that greater numbers would have died of cold and starvation as the parcels often included tea, condensed milk, jam, dried fruit, meat and cheese, as well as cigarettes and pipe tobacco. It is to be hoped that those parcels found their way to the prison camps where Sidney and his fellow members of 1st RMLI were held.

Sidney Herbert Martin was repatriated on 5 January 1919.

At the time of writing I do not know if or how he was injured but Sidney died on 15 May 1920 aged 39. The official cause of death was nephritis, which he’d had for 67 days, and cardiac failure but we have to ask ourselves what effect his experiences in the trenches and in the prisoner of war camp had on his physical and mental health. Such experiences cannot but change a person and we know that many soldiers of the First World War, whilst escaping with their lives, returned home with what would now be termed Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

His son was just six when Sidney died and never got to know him, nor was much, if anything, spoken about Sidney within the family. I hope that, in setting the scene for Sidney’s service in the Royal Marines Light Infantry, I have been able to shine a light on him and perhaps on why he may have been one of those men who did not speak of their experiences when they arrived home from the trenches or the prisoner of war camps.

The Royal Naval Division Monument at Gavrelle

The monument sits at the entrance to Gavrelle village from the main Arras – Douai road.

It depicts the house to house fighting which took place there, showing a large naval anchor (the emblem of the division) in the ruins of a red brick house, with a number of shells lying amongst the fallen bricks.

There are plaques to all the units of the Division on the outer wall.

The anchor came from a sunken British naval vessel and was donated by the RN Mooring and Marine Salvage depot at Pembroke dock. At the time of the war, the houses in Gavrelle were built of red bricks.

The monument was constructed to a specific height which symbolised the highest feature of the village which survived above ground after the battle.

In 1923, in a foreword to the official account of the RND’s actions, Winston Churchill wrote:

“By their conduct in the forefront of the battle, by their character; and by the feats of arms which they performed, they raised themselves into that glorious company of the seven or eight most famous divisions of the British Army in the Great War.”

But this was at great cost as can be seen in the Commonwealth War cemeteries along the Western Front, where the seried ranks of army corps and regimental badges are broken by the symbols of furled anchors marking the resting places of the remains of the members of the Royal Naval Division.

Four sailors’ graves from the Royal Naval Division in the Point-du-Jour cemetery near Gavrelle

I have tried to understand what brought Sidney Herbert Martin, PO/1556/S, to Gavrelle and the circumstances which led to him and his fellow members of the Royal Naval Division, ‘the sailors in khaki’, being killed, wounded or taken prisoner there.

I am left, yet again, with great sadness at the effect of that war on the men and women of a whole generation. And on the generations which followed.

My brother in-law is not the only person to have wondered what happened to their grandfather and to question why no one in the family knew anything about what happened to them.

I hope I have answered some of the questions and shown Vince that he had a grandfather to be proud of and that it would have been an honour to know him.

I am a family historian, not a military historian but yet again my research has taken me into the battles of the Western Front in World War 1. I have sought to assimilate a great deal of information from many sources and have represented the events which took place to the best of my ability. And I apologise if I have inadvertently omitted any of those sources from the list below.

Susan Morris

Next: Martin family tree

Notes

24 years after the 1915 Registration, National Register of the whole population, irrespective of age, was compiled in September 1939 for use during World War 2, for identity cards, rationing and conscription.

Unlike the 1915 National Register, which was ordered to be destroyed in 1921, the 1939 Register is held in the National Archives and the forms have recently been released, though with the details of anybody born after 1915 redacted (to preserve privacy).

The 1939 Register was used as the basis of the National Health scheme in 1948.

* Depending on which website/calculator is used, £15 would be worth between £542 and £768 at today’s date.

Sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Recruitment_to_the_British_Army_during_the_First_World_War

https://derbyscheme.wordpress.com/2013/01/19/national-registration-act-1915/

https://greatwarlondon.wordpress.com/2015/08/25/national-register/

Britain’s Sea Soldiers, A record of the Royal Marines during the war 1914 – 1919

by General Sir H E Blumberg, KCB, Royal Marines

http://www.1914-1918.net/msa1916.html

http://www.1914-1918.net/recruitment.htm

http://search.findmypast.co.uk/search-world-records/royal-naval-division-records-1914-1919

http://wereldoorlog1418.nl/RND-Royal-Naval-Division/index.html

http://www.royalnavaldivision.co.uk/?page_id=10

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/63rd_(Royal_Naval)_Division

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operations_on_the_Ancre,_January%E2%80%93March_1917

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Arras_(1917)

http://www.webmatters.net/txtpat/?id=214

http://www.ozanne.co.uk/content/battle-gavrelle-arras-april-1917

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/1577088/Online-tribute-to-Winstons-Little-Army.html

https://community.dur.ac.uk/4schools.resources/FWW3/arras.htm

http://talkinghistory1914.blogspot.co.uk/p/blog-page_14.html

Battleground Europe Series – Gavrelle Arras by Kyle Tallett and Trevor Tasker, published by Pen and Sword

The Western Front Association – Heilsberg POW camp